フリージャーナリスト髙岡海志氏(テンプル大学)の取材記録【Rethinking the Status Cow ~その牛の在り方を再考する~】(全日本・食学会シェフ牛事業の取り組み)が、『日本外国特派員協会』主催の若手ジャーナリストを育成する「The Swadesh DeRoy Scholarship(スワデシュ・デロイ奨学金)2022」でphoto(写真)部門で優勝されました。

食学会で数年にわたりジャージー牛の肥育から食肉となるまでを追った記録です。記録写真とともに、食学会活動の意図、経過が紹介されています。

※発表論文は英文のため、日本語訳も添付しております。

写真とともにぜひご一読ください。

Kaiji Takaoka

This four-part photo essay documents an experiment by the All-Japan Food Association (AJFA) on an alternative method of breeding, raising, fattening, and slaughtering beef cattle. The current Wagyu system in Japan is rife with inefficiencies, absurd food mileage, and an enormous environmental footprint. Their experiment featured Kanta, a jersey bull raised on Hachijo-jima. Bulls born on dairy farms are usually killed at birth but the AJFA instead chose to raise him, fatten him up, in an effort to combine the dairy and the beef industry, thereby creating a more holistic and sustainable process. To do this they shortened the supply chain by limiting the need for middlemen and was sold directly to chefs and restaurants.

On the island of Hachijou, an island south of Tokyo, Jersey cattle and F-1 (Holstein and Wagyu Hybrid) roam on vast pastures. Due to this it is possible to have their diet consist of local grass supplemented with imported hay. The All-Japan Food Association has raised three cows here over the past two years, all of them Jersey cattle, two female cows that had given birth multiple times and one jersey bull (Kanta) who I followed on the mainland.

F-1 Hybrid cows lounge around Fure-ai Bokujou, a farm and pasture which is open for locals and tourists. Hachijou-jima attracts fisherman and divers because of its volcanic rock formations below sea and abundant sea-life.

A calf and presumably its mother graze. According to Mr. Takaoka, a representative for the All-Japan Food Association and an expert in Wagyu, it is common for Wagyu brands such as Matsuzaka buy and ship calfs from Okinawa to raise them and fatten them up on their farms. The distance between the two is 1268 km. On the other hand, for this experiment, Kanta and the other two jersey cows where born and raised 287 km from the special wards of Tokyo but still technically in prefectural Tokyo.

Another pasture on Hachijou-jima. This pasture extends from the white fence all across the face of the mountain. This was where Kanta, the bull I followed was raised.

Cows have a large expanse of land to roam here in Hachijoujima, unlike dairy farms in Tokyo or certain other parts of the country where they are kept in pens and hardly get any exercise

A golf course repurposed to become a dairy farm, this pasture is home to exclusively jersey cows.

Jersey cows wait at the gate to be milked. Because of the regular schedule, they already know when they should come near the gate.

Workers prepare local grass and supplemental imported grass for the cows to keep them occupied while others are milked. Since each cow has a name and they remember it, they wait and eat until their name is called.

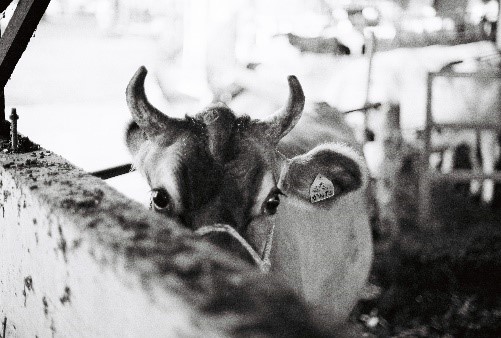

A cow looks on as workers prepare the feed.

A worker calls a cow over to be milked. It comes promptly.

These cows are usually milked two times a day, sometimes three depending on their level of lactation.

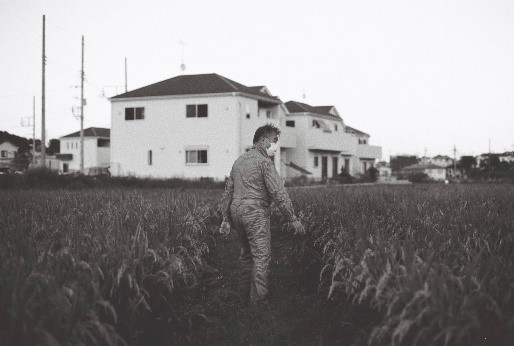

In late 2020, Kanta was moved to Isonuma Dairy Farm, located in the outskirts of Tokyo (Hachioji). Isonuma Dairy Farms is also an outlier among dairy farms since cows here are able to roam somewhat more freely, with slopes and inclines to get the cattle to exercise. Here Kanta's diet consisted of hay and eco-feed, repurposed food scraps from factories and sometimes even breweries. He spent close to a year, eating and being fattened up until he was sent to the slaughterhouse. In some cases Wagyu cattle could be shipped nationwide from Okinawa to Hokkaido in some extreme cases, to be fattened up. Kanta's journey from Hachijo-jima to Hachioji reduces the emissions and the food mileage that may occur during the normal process.

Kanta, the jersey bull, in his enclosure the morning of his slaughter. According to Mr. Isonuma (the owner of the farm) he was exceptionally large for a jersey cow, larger than the previous two that had passed through his farm.

Pineapple scraps, leafy scarps, hardened miso, beer wort, a variety of food could be found in their diet. This limits the need for various water-intensive grains shipped from overseas that consist a large part of a Wagyu cow's diet.

A sign that reads "Vegetable Scraps for the Cows". Isonuma Dairy Farm also has a garden which they use to grow produce. Any waste or unusable products are included into the cow's feed.

A pile of eco-feed ready to be fed to the cows.

Isonuma Farms also boasts a huge number of cow species. In this picture alone, three species of cows are present but in the whole farm seven are present, which Mr. Isonuma suspects is a world record.

Mr. Isonuma has been raising cows for his whole life, inheriting the farm for his father. At first he raised, milked, and bred them in the traditional way, in small pens with limited exercise. But when he was twenty-years-old, he visited Austrailia and saw their method of open-pasture farms and tried to emulate it the best he could in Tokyo.

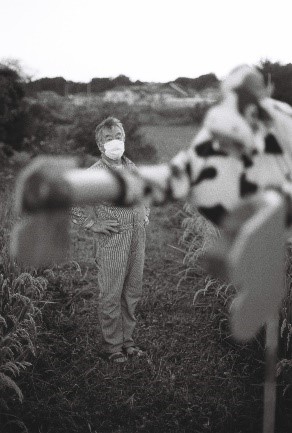

Thus he created his own hybrid system and became more invested improving the conditions of his animals. On top of that he also grows rice, pictured here, and has various different vegetable gardens scattered on his farm, on any space not inhabited by a cow.

Kanta led into the truck that would transport him to the slaughterhouse.

Kanta at Agris-One, a slaughter house located in Wako, Tokyo. They mostly slaughter Wagyu cattle and today Kanta was the only non-Wagyu cattle there.

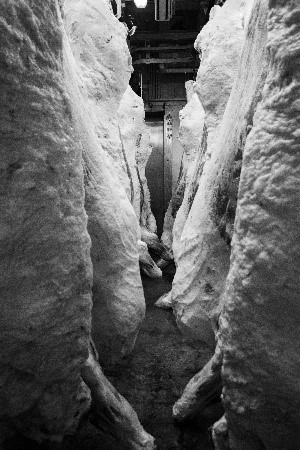

Photography was not allowed in the slaughterhouse but I was able to take a few pictures of the carcass afterwards. It was kept there for a day and then shipped to Maruyoshi Shouji, a meat packaging factory right outside of Tokyo where it underwent a process similar to dry-again known as karashi. This was unusual as it skipped the market place and went directly to the meat distributor, eliminating the need for extra transportation and additional food mileage.

Wagyu carcasses hang from the ceiling, waiting to be shipped to marketplaces where they will be sold to the highest bidder.

One of the biggest Wagyu marketplaces, Shibaura-Shijou, is located in Tokyo and gather Wagyu and buyers from all over the country. According to Mr. Hirai, the buyer for Murayoshi Shouji, this is most likely due to the discrepancies of market volume around the farms raising the Wagyu and Tokyo. The farms raising Wagyu tend to be in more rural areas and the market can become quickly saturated and not as profitable if they sold their product there. However, if they were to bring their produce to Tokyo, where the market is much bigger, prices are more competitive and the farmers would be able to sell their product at a higher price.

Due to the distance Wagyu produce must travel to be sold, this increases the food mileage once again and contributes to more emissions into the atmosphere.

Here, Kanta's fat had a noticeable yellow tinge to it than the other carcasses visible in the background. This is most likely due to the variety of food he was fed according to Mr. Okamoto, the head of operations at Agris One.

Pictured here, Kanta's carcass was also remarkably small compared to the others, reaching 360 kilograms while others reached 500 or sometimes even more. Wagyu diets are filled with excessive carbohydrates which lead some to develop diabetes. Some become blind and their intestines can develop issues and scarring. Kanta's intestines were pristine and passed inspection without a hitch.

At Murayoshi-Shouji, Mr. Hirai and Mr. Takaoka inspect the marbling on Kanta's carcass. According to them, it is surprisingly well-marbled even when not undergoing a vitamin reduction that Wagyu cattle usually go through a few weeks before their slaughter. Vitamin reduction may increase marbling, but it also deteriorates the health of the cow.

A worker debones the belly of Kanta's carcass, this will be used by an Italian restaurant to make a packaged beef stew.

A finished belly is ready for further processing while the worker prepares the next cut of beef.

A worker prepares to clean and process the t-bone/porterhouse section of Kanta.

Jersey beef hardly found its way to a restaurant table unless minced and put into a sausage. In other words it was considered a low-quality beef. But this time, after the beef was processed, it was shipped to several restaurants which were part of the All-Japan Food Association's network. Kakunoshin-F (a restaurant that specializes in dry-aged beef) got some of the intestines, Ningyocho Imahan Banyo (a Japanese restaurant that specializes in sumibi-yaki Wagyu steak, and Wakiya Turandot (a Chinese restaurant). Each restaurant and chef approached the Jersey beef differently and in their own way attempted use all of the beef's potential.

A chef of Kakunoshin-F, a speciality dry-aged beef restaurant checking to see how cooked the slices of liver are. The liver was then sliced and finished with browned butter sauce with a side of potatoes for a rustic feel. The chef of the restaurant, Mr. Endou was astonished since the liver was very smooth and fatty. There was hardly any iron-like taste that puts some people off liver and instead was similar in flavor and mouthfeel to fois gras. When asked for a possible explanation, Mr. Endo joked "Maybe it's from eating so much pineapple."

Another dish from Kakunoshin F, a sausage made from the cecum of Kanta's intestines. As with the liver dish, the sausage did not have as strong of an intestine smell as would have been expected. Mr. Endo also noted that, "normally, we would have to cover up the smell of the intestines with onions and other spices but this time it wasn't the case." He wondered if it was due to the type of feed or the fact it was Jersey.

From the top, the liver, heart and the cecum intestine of Kanta, ready to be cooked and plated. Multiple other dishes were served including Tripe simmered in Tomato Sauce (Trippa), Giara simmered in White Wine, and Green Salad topped with heart. Each dish attempted to bring out the best of the cut.

Head Chef of Ningyocho Imahan Banyoh, Motohiro Muraoka starts cooking the t-bone steak over a bed of hot charcoals. This restaurant specializes in Wagyu sumiybi-yaki steaks, sukiyaki, shabu-shabu, and kaiseki.

Two cuts of Kanta cook on the charcoal grill.

When asked what he thought about the Jersey beef, he responded enthusiastically, "I never knew that it could be this delicious. It's to lean and still flavorful. At this restaurant, we don't really use anything other than Wagyu so it was such a shock. It taught me so much." Since this picture was taken, Chef Muraoka has developed the steak further, marinating it in amazake and finishing it with compound butter made from Jersey Milk.

The steak was cooked to medium, Chef Muraoka commenting that it's best way to activate all the flavor in the beef.

The finished T-Bone Steak ready to be served to customers. Despite grass and alternative feeding methods, the meat had a very clean flavor profile. Usually grass-fed beef has a sort of earthiness that is very characteristic of it but in Kanta's case, it was surprisingly clean.

Wakiya Turandadot is run by Chef Yuji Wakiya, a world-famous chef that specializes in Haute-Chinese cuisine. For several years he has worked with the All-Japan Food Association to use more Jersey cows at his restaurant.

This dish is called 水煮牛肉 or Water-Boiled Beef. It has its origins in the Sichuan region and tends to cook tough cuts of meat for long periods of time to soften them. At Wakiya, beef tendons were steamed for 3 hours until tender and bursting with collagen. Along side, seasonal vegetables such as mushrooms and eggplant where added in the soup with chillies giving the characteristic Sichuan spice.

The finished water boiled beef. The umami flooding out of each bite of the beef was well-balanced with the spice of the chillies creating a harmony between with the vegetables coming along for the ride.

Kaiji Takaoka (born in Tokyo in 1998.)

Work Experience

Started food business,Freelance journalist,Video Direction,Photographer

Education

While at Temple University